How can a family be a demolition of the self and a home one lives in?

How does a fractured body heal a trauma through connection?

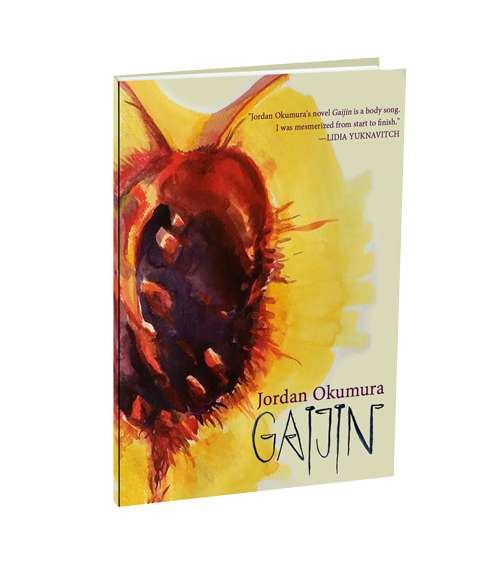

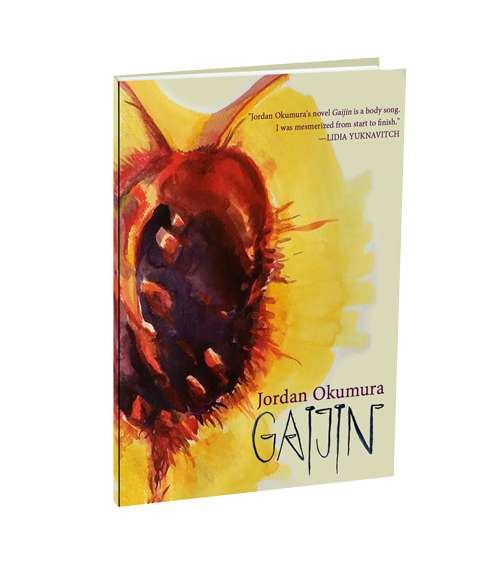

Deeply embedded in the novel Gaijin, by Jordan Okumura, is an

unsettling nostalgia for family, haunted by whispers and by

abandoning, by illness and isolation, by silence and trauma. The

novel attempts to simultaneously track a personal rupture and a

family, through the painful and awkward reclamation of the self after

sexual violence and the evocation of a patriarch who is half dreamed,

half real. The narrative bravely plows forward in reconciling two

disparate sources of grief in order to heal them, trying to articulate the

inarticulatable in a style that straddles genres-part memoir, part

mythology, and part eulogy to a grandfather.

How can a family be a demolition of the self and a home one lives in?

How does a fractured body heal a trauma through connection?

Deeply embedded in the novel Gaijin, by Jordan Okumura, is an

unsettling nostalgia for family, haunted by whispers and by

abandoning, by illness and isolation, by silence and trauma. The

novel attempts to simultaneously track a personal rupture and a

family, through the painful and awkward reclamation of the self after

sexual violence and the evocation of a patriarch who is half dreamed,

half real. The narrative bravely plows forward in reconciling two

disparate sources of grief in order to heal them, trying to articulate the

inarticulatable in a style that straddles genres-part memoir, part

mythology, and part eulogy to a grandfather.

Desperate to connect, the narrator of Gaijin feels as distanced from her Japanese heritage as she does from the love of her family. But she can dream, reach for. The narrator feels the momentum of histories across her familial generations, from grandfather to granddaughter and even, at times, from father to daughter; how we are tied to each other's stories, how they shape the story we think we are creating ourselves. Through exquisitely meticulous description, Okumura describes a longing mythical in proportions, but grounded in the body that receives and aches to connect, to belong. The narrator experiences, for example, the Japanese characters of her grandparents not as mere code for a language she can not access, but as a 3-dimensional conjuring of fantastical creatures, stilled and waiting to awaken from the page and into her world, much like the narrator, who tries to provoke her own dreamed reality into being.

The very name of the novel Gaijin, means foreigner in Japanese. And it connotes the concepts of insider and outsider, pointing to the narrator's lack of belonging. She feels an outsider to her own culture and her family, and at times, to her own self. But it also points to her need to protect herself from who she lets in, and to the sexual violence she is constantly framing and reframing in attempts to yield power over trauma. She has become foreign to herself and she is determined to rewrite over the wounds, determined to reclaim the self.

Laced throughout the narrative of Gaijin is mention of Momotaro, or The Peach Boy, the protagonist of a heroic Japanese fairytale who the narrator longs to be like. The peach boy is a gift delivered to his parents whose wishes for a son are answered when he is born from a peach. The boy isn't quite mortal, isn't quite real. But still, in juxtaposition to the narrator, the peach boy achieves belonging and respect and the undying love of his parents without question. His strength to overcome enemies is superhuman. Maybe the narrator can be as heroic as the peach boy. Maybe she can be as loved.

Exquisite and excruciating, Gaijin, a first novel for Okumura, is unique in its accomplishment of employing strongly metaphoric language, with a narrative deeply rooted in the concrete realities of a daughter, a granddaughter, a woman, a survivor. It is a blunt and alarmingly honest accounting of scars and blows to the spirit, with words piling up against voicelessness, and a persistent refusal to descend into despair. So powerful is the poetry and aching of Gaijin, it crushes the breath out of you as you read, cracks your chest wide open. Though the sum of Okumura's exquisite metaphors is often grim, tragic, there is always a glimmer in the yearning.

Jordan Okumura is a writer and editor. Her work has been published in Gargoyle, DIRTY:DIRTY (Jaded Ibis Press), Black Rabbit, and First Stop Fiction. Jordan lives and works in Sacramento, California where she is an editor for trade news publications in the agricultural industry and is a regular contributor at Enclave/Entropy. Gaijin is her first book.

Jordan Okumura is a writer and editor. Her work has been published in Gargoyle, DIRTY:DIRTY (Jaded Ibis Press), Black Rabbit, and First Stop Fiction. Jordan lives and works in Sacramento, California where she is an editor for trade news publications in the agricultural industry and is a regular contributor at Enclave/Entropy. Gaijin is her first book.